Your Colon or Rectal Pathology Report: Invasive Adenocarcinoma

Biopsy samples taken from your colon or rectum are studied by a doctor with special training, called a pathologist. After testing the samples, the pathologist creates a report on what was found. This pathology report can then be used to help manage your care.

The information here is meant to help you understand some of the medical terms you might see in your pathology report after your colon or rectum is biopsied.

(If you have colon or rectal cancer and have surgery to treat it, a separate pathology report would be created after testing the part of the colon or rectum that was removed. That report might contain some of the same information below, as well as other information.)

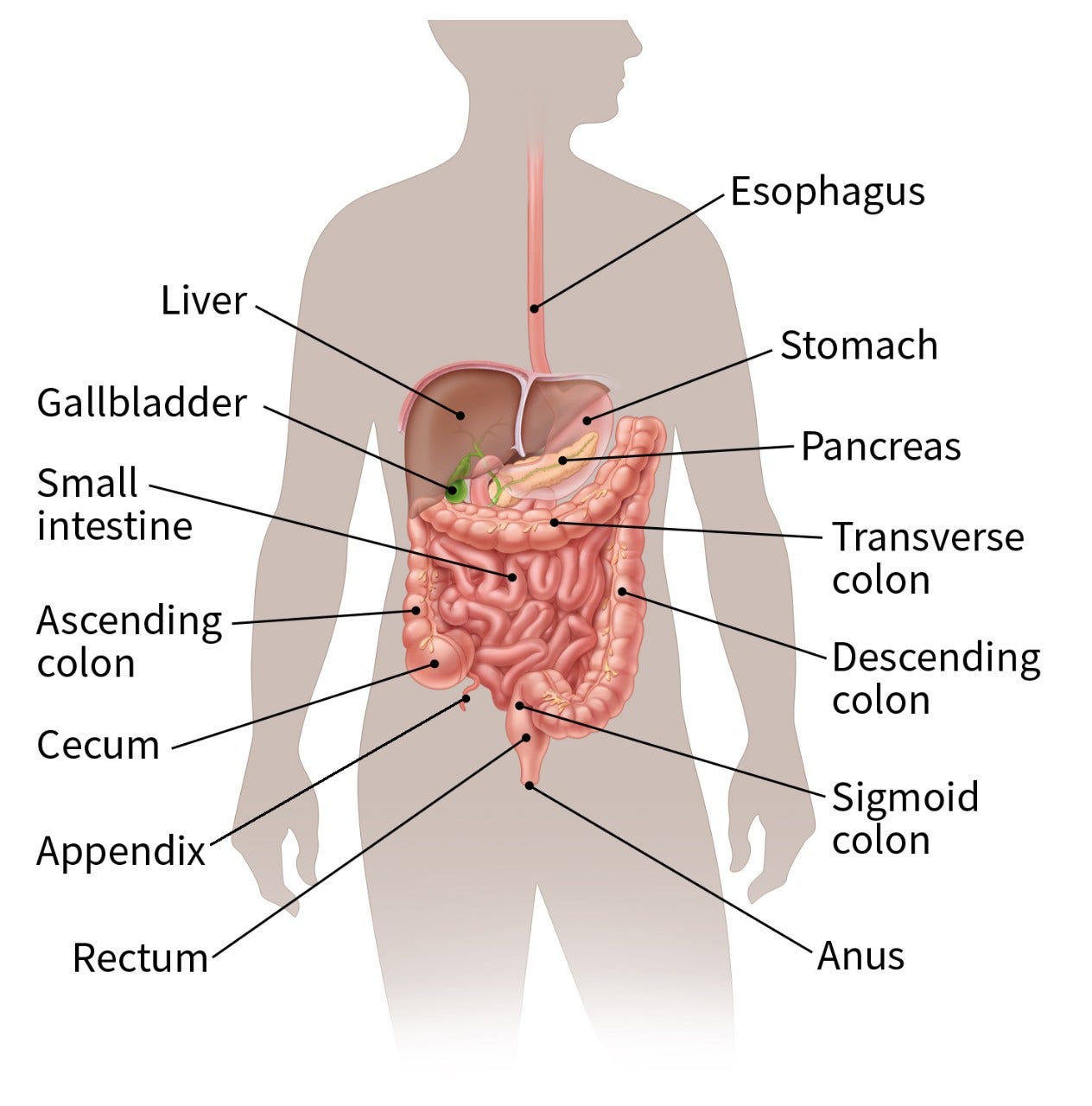

Parts of the colon and rectum

The colon and rectum make up the large intestine (or large bowel), which is part of the digestive system. The cecum is the beginning of the colon, where the small intestine empties into the large intestine. The ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon are the parts of the colon after the cecum. The colon ends at the rectum, where waste (stool) is stored until it leaves the body through the anus.

Types of colon or rectal cancer

Carcinoma

Cancers that start in the cells that line the insides of organs such as the colon or rectum are called carcinomas. Most cancers that start in the colon or rectum are carcinomas (specifically adenocarcinomas – see below).

If a carcinoma is described as infiltrating or invasive, it means the cancer cells have grown deeper than the top layers of the inner lining of the colon or rectum (known as the mucosa), so this is a true cancer (and not a pre-cancer). At this point the cancer cells can grow through the wall of the colon or rectum and into nearby structures, or they might spread to nearby lymph nodes and other parts of the body.

But being infiltrative or invasive doesn’t always mean that the cancer has grown deeply into the wall of the colon or rectum. A biopsy samples just a small part of a tumor, so it can’t always show how deeply the tumor has grown into the wall. To know this, the pathologist needs to see the entire tumor after it is removed during surgery.

Adenocarcinoma of the colon (or rectum)

Adenocarcinoma is a type of cancer that starts in the gland cells that make mucus to lubricate and protect the inside of the colon and rectum. This is the most common type of colon and rectum cancer.

Other tumors or cancers in the colon or rectum

Other types of tumors or cancers can also start in the colon or rectum, although these are much less common than adenocarcinomas. They include:

- Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), including carcinoid tumors

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphomas

Other information in the report if colon or rectal cancer is found

If colon or rectal carcinoma (cancer) is found, the pathology report might have other information about the cancer.

Cancer grade (differentiation)

If cancer is found, the pathologist will likely assign it a grade, based on how abnormal the cancer cells look under a microscope. Colon or rectal cancer is usually given 1 of 3 grades:

- Well-differentiated (low grade)

- Moderately differentiated (intermediate grade)

- Poorly differentiated (high grade)

Sometimes, though, only 2 grades are used to describe it: well/moderately differentiated (low grade) and poorly differentiated (high grade).

Poorly differentiated (high-grade) cancers tend to grow and spread more quickly than well and moderately differentiated cancers.

The grade of the cancer is one of many factors used to help predict a person's prognosis (outlook). However, other factors are also important, such as if the cancer cells have certain gene or protein changes, and how far the cancer has grown or spread (which can’t be determined from the biopsy).

Vascular, lymphatic, or lymphovascular (angiolymphatic) invasion

These terms mean that the cancer has grown into the small blood vessels and/or lymph vessels of the colon or rectum, so there is a higher chance that it could have spread outside the colon or rectum. However, this doesn’t mean that the cancer has spread.

Having this type of invasion might affect what type of treatments are recommended after the cancer is removed, so discuss this finding with your doctor.

Mucin or colloid

Gland cells make mucin to help lubricate the colon. Colon cancers (adenocarcinomas) that make large amounts of mucin are referred to as mucinous or colloid adenocarcinomas. Typically, when this is mentioned on a biopsy report, it doesn’t affect treatment.

If the report also mentions a polyp or polyps (along with carcinoma)

A polyp is a projection (growth) from the inner lining into the lumen (hollow center) of the colon or rectum. Colon and rectal polyps are common.

Most polyps are benign (non-cancerous) growths, but cancer can start in some types of polyps. For example, hyperplastic polyps are typically benign (not cancer or pre-cancer) and are not a cause for concern. But other types of polyps, such as adenomatous polyps (adenomas) might turn into cancer, so they need to be removed. (To learn more, see Understanding Your Colon or Rectal Pathology Report: Polyps.)

Still, if polyps are present in addition to cancer elsewhere in the colon or rectum, they don’t usually affect the treatment or follow-up of the cancer.

Biomarker tests on biopsy samples if cancer is found

If colon or rectal carcinoma (cancer) is found in the biopsy samples, the cancer cells might be tested to see if they have changes in certain genes or proteins. These are sometimes called biomarker tests.

For example, tests might be done to look for:

- Changes in the KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF genes

- Changes in mismatch repair (MMR) genes, such as MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2

- The level of microsatellite instability (MSI) in the cancer cells

- The level of tumor mutational burden (TMB)

- Levels of the HER2 gene or protein

- Changes in the NTRK genes

The results of biomarker testing can often help tell if certain cancer medicines – especially targeted drugs and immunotherapy – are (or are not) likely to be helpful.

For more on these tests, see Tests to Diagnose and Stage Colorectal Cancer.

Testing for MSI and/or defects in mismatch repair genes (dMMR) can also have another purpose. (These results are often related, in that finding MSI means that there is probably a change in one of the MMR genes as well.)

Having an inherited defect in an MMR gene can lead to a condition called Lynch syndrome or hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC). If your cancer cells have MSI or a defect in an MMR gene, your doctor may recommend genetic counseling and testing to see if you have Lynch syndrome. (Finding an MMR gene change in cells other than cancer cells can confirm that you inherited the change from your parents and that this change is in all the cells in your body.)

Along with having a high risk for colon cancer, people with Lynch syndrome have an increased risk for some other cancers. Any other family members who have inherited the same gene change are also at increased risk for these cancers.

- Written by

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

Last Revised: July 7, 2023

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.