ACS Research News

Published on: February 10, 2026

Your state can can help protect you from cancer with policies, programs, and campaigns to reduce risk factors and support cancer screening.

Published on: January 22, 2026

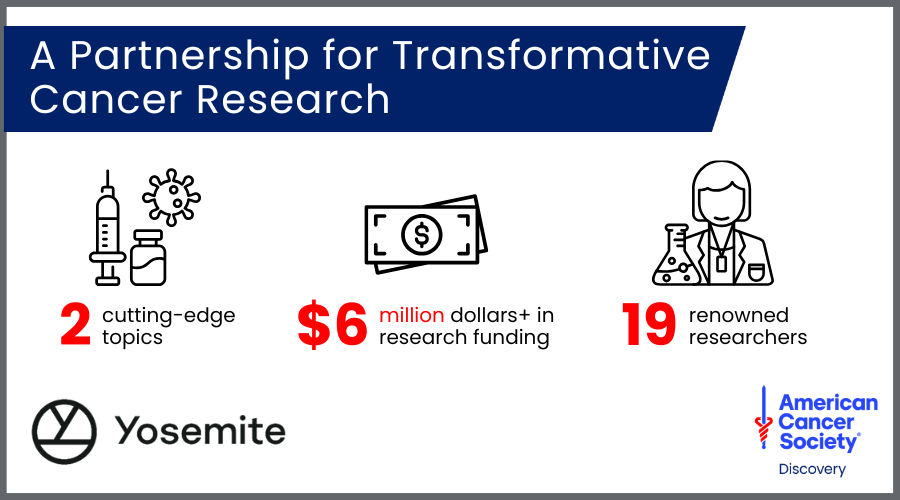

Awardees will receive $330,000 grants co-funded by Yosemite and the American Cancer Society to pursue critical cancer research.

Published on: January 13, 2026

Milestone in cancer survival: 7 in 10 people reach the 5-year mark

Published on: December 4, 2025

The updated guideline for cervical cancer screening introduces the option of self-collection of vaginal samples for HPV testing and new guidance on when screening can end.