New Lung Cancer Screening Guideline Increases Eligibility

The updated ACS guideline recommends adults ages 50-80 who have a 20+ pack-year smoking history get screened with a low-dose CT scan each year.

The new lung cancer screening guideline, published in the ACS flagship journal, CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, recommends that primary care or specialty care providers refer 50 to 80-year-olds for yearly screening with LDCT if they currently smoke or used to smoke, have a 20-pack-year or more smoking history, without any symptoms of lung cancer. People should not be screened if they have serious health problems that will likely limit how long they will live, or if they won’t be able to or won’t want to get treatment if lung cancer is found.

The guideline also calls for health care providers to have a shared decision-making conversation that explains that the leading organizations agree on the value of lung cancer screening and includes the benefits, limitations, and harms of screening with LDCT, smoking-cessation counseling, and offer available interventions to help people who are currently smoking to quit.

This guideline aims to reduce the number of deaths from lung cancer. Each year, more people in the United States die from lung cancer than from colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined. If lung cancer is found at an earlier stage, when it’s small and before it has spread, it’s more likely to be treated successfully.

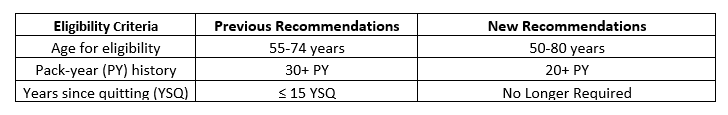

The updated lung cancer screening guideline qualifies more people to get an LDCT scan each year.

It’s critical to both help health care providers identify people who are eligible for screening and to increase awareness among people who currently smoke or formerly smoked to talk with their health care providers about lung cancer screening.”

Featured Term: Pack-Year History

Pack-year history describes how long a person smoked traditional, combustible cigarettes and how many they smoked. One pack of cigarettes contains 20 cigarettes. To calculate the number of pack years, multiply the number of years a person smoked by the number of packs they smoked each day.

The new ACS lung cancer screening guideline says anyone with a 20-pack-year history or more qualifies for getting a yearly low-dose CT scan to screen for lung cancer. A person could have a 20-pack-year history, for example, if they smoked:

- 1 pack a day for 20 years

- 2 packs a day for 10 years

- 1 ½ packs a day for a little longer than 13 years

- 3 packs a day for a little longer than 6 ½ years

These changes in the guideline mean that nearly 5 million more people will be eligible for lung cancer screening each year:

- People aged 50 to 80 years who currently or formerly smoked should talk with a health care provider about lung cancer screening. (Previously, the ACS guideline was ages 55 to 74 years.)

- People with lower pack-year histories qualify for screening. The new guideline recommends screening for anyone with a 20+ pack-year history. (Previously, the ACS guideline had a 30+ year pack history).

- The most important change in the updated guideline is that the number of years since quitting smoking is no longer a qualifier for starting or stopping yearly screening. That means a person who used to smoke with at least a 20 pack-year history, whether they quit yesterday or 20 years ago, is considered to have a high risk for developing lung cancer and should be recommended for a yearly LDCT scan if they don't have a serious health problem that will likely limit how long they will live, or if they won’t be able to or won’t want to get treatment if lung cancer is found. (Previously, the ACS guideline recommended only people who had quit 15 years ago or less.)

These changes mean that many people who started screening will not lose eligibility by reaching 15 years since they quit. This is important because their risk of lung cancer is still rising due to increasing age.

The last change also means those who have a 20+ pack-year history and reach their 15th year since quitting before age 50 will now be eligible to start and continue screening.

Picture a business executive in her 50s who previously smoked 2 packs a day throughout high school and into young adulthood while she attended college and graduate school, and who quit when she became a parent at age 30. Even though the time she smoked feels in the distant past, she still has a smoking history of 20 pack-years, and her risk of lung cancer will never be as low as a person her age who never smoked. Now—for the first time ever—she’s considered a candidate for lung cancer screening to reduce her chance of developing significant health problems from lung cancer or dying from it.”

The new lung cancer screening guideline also emphasizes the importance of shared decision-making about screening and counseling to help people quit using cigarettes.

“The number one reason people give for not getting a lung cancer screening test is that their health care provider didn’t talk to them about it at all, or didn’t talk to them thoroughly,” says Robert Smith, PhD, the Sr Vice President for Early Cancer Detection Science at ACS.

Interestingly, studies have shown that other methods—including video and online educational interventions, pre- and post-intervention surveys, and using decision aids on a patient portal—were not as effective as an empathetic, comprehensive conversation with a health care professional.

“Studies show that screening behavior is more nuanced than a provider making a simple recommendation,” the guideline authors say. “Rather, the quality and content of the communication around the recommendation are significant and have an important influence on a patient’s decision to get screened.”

The guideline calls for shared decision-making between patients and a qualified health professional. Additionally, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require shared decision-making as part of counseling before referring Medicare beneficiaries for screening.

The guidance for those shared decision-making discussions include:

Help to Stop Smoking

- Evidence-based smoking-cessation counseling if the patient currently uses cigarettes

- Offering interventions and connection to smoking-cessation resources

Explanation of the Lung Cancer Screening Process

- Explanation of the purpose of lung cancer screening

- Overview of the consensus among leading cancer care organizations on the recommendations that endorse lung cancer screening

- Overview of the screening process and the importance of consistent, yearly screening

Focus on the Patient’s Personal Risk and Preferences

- Individualized assessment of the patient’s current health status and conditions. People with health conditions that substantially limit their life expectancy (or who are unable or unwilling to undergo more testing as well as treatment if scans reveal tumors) should not be referred for screening with LDCT.

- Conversation about the benefits, risks, and harms of screening for lung cancer that allows time for the patient to talk about their values and preferences

To help improve patients getting lung cancer screening, health care providers can work toward having an office policy on how to conduct lung cancer screening discussions that include a team-based approach to assess eligibility and risk and to set up referrals to screening. They can also refresh the education of all patient-facing staff to counter misconceptions about the benefits of screening and talk through concerns about potential harms, such as incidental findings.”

Some of the highest lung cancer screening rates are achieved in settings where the provider can refer the patient to a clinic where everything is managed under one roof: risk assessment, shared decision-making, smoking-cessation support, screening referral, and follow-up tracking.

Patient preferences also influence their decision to follow through on screening. For instance, one report showed that people with a higher risk or with a longer life expectancy (10 years or more) are more likely to get screened and are less dissuaded by descriptions of the potential downsides.

This updated guideline will increase the number of people eligible for lung cancer screening, but that alone isn’t enough.

The guideline authors urge accelerated implementation of screening and smoking cessation programs, and that these programs embed themselves in communities that include populations affected by lung cancer disparities, such as racial minority groups and rural residents.

“The good news is that decades of successful efforts focused on decreasing the number of people who start smoking and supporting people who smoke to quit has led to declines in the incidence of lung cancer and death from it,” Smith says.

But the burden of the disease will remain very high for years to come, as tens of millions of people with a history of smoking reach the ages when lung cancer risk rises.

We can help prevent many people from dying of lung cancer if, as a health care community, we embrace the urgent challenge to improve our ability to identify the population at risk and apply our knowledge to achieve high rates of participation in yearly lung cancer screening"

This update aligns with recently updated recommendations for annual lung cancer screening from the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the American College of Chest Physicians.

In addition to Robert Smith, PhD, other ACS authors of this guideline include: William Dahut, MD, Deana Baptiste, PhD, MPH, Tyler Kratzer, MPH, and Karli Kondo, PhD, MA.

- Helpful resources

- For researchers

American Cancer Society news stories are copyrighted material and are not intended to be used as press releases. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.