Study: Premature Deaths from Cancer in One Year Led to Loss of 8.7 Million Years of Life and $94 Billion of Future Earnings

An artistic representation of tumor-circulating DNA in the blood

Cancer kills many people before their time, costing more than 8.7 million years of life among people aged 16 to 84 in the United States in 2015. Researchers estimate cancer also leads to $94 billion in future lost earnings, not just in 2015. These numbers come from a new report by American Cancer Society (ACS) researchers in JAMA Oncology.

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the US and expected to cause more than 606,880 deaths in 2019. Beyond the loss felt by loved ones, these deaths cut earning years short, reducing the work force and leading to a big economic burden. Calculating lost years of life and lost earnings is a common approach that researchers use to make the economic and social costs of premature deaths clearer to decision-makers, who can use this data to help set health policies and prioritize budgets and resources for cancer research, as well as for prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment. Compared to other studies, this one used more recent data and estimated losses at the state level as well as nationally.

Investigators led by Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, calculated person-years of life lost using numbers of cancer deaths and life expectancy data in people aged 16 to 84 years who died from cancer in the US in 2015. The researchers added all the years each of the 492,146 people were expected to live if they’d never developed cancer to estimate there were a total of 8,739,939 life years lost.

Farhad, scientific director of the surveillance and health services research program at the ACS, and his colleagues estimated cancer deaths overall and for the major cancers. Overall lost earnings were $94.4 billion, and $191,900 per each person that died from cancer. The researchers found that the highest lost earnings were from:

- lung cancer ($21.3 billion)

- colorectal cancer ($9.4 billion)

- breast cancer in women ($6.2 billion)

- pancreatic cancer ($6.1 billion)

The authors pointed out that these cancers are linked with risk factors that people can potentially change to lower their chances of developing cancer. The lost-earnings estimates do not include other costs associated with cancer, such as costs of treatment and informal caregiving.

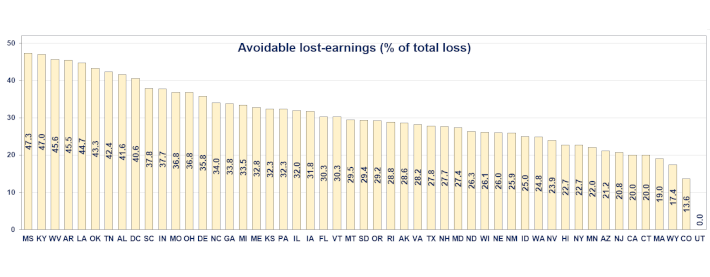

Lost earnings were highest in the South and lowest in the West. For example, they ranged from $35.3 million per 100,000 people in Kentucky to $19.6 million in Utah. If all states had the same rate as Utah, lost earnings would have been $27.7 billion lower – almost 30% – and life years lost would have been 2.4 million less.

Islami said, “This suggests that a big part of our current national burden from cancer deaths is potentially avoidable.” He said healthcare providers, for example, can help prevent cancer by referring patients to programs, like those for smoking cessation and for improving diet and physical activity.

Robin Yabroff, PhD, senior author of the study, added, “These findings have implications for health policy makers. Health insurance coverage, which varies substantially by state, is one of the strongest predictors of access to care. Ensuring equitable access to high-quality care through increased health insurance coverage options could reduce differences in the burden of cancer across states. Medicaid expansion, in particular, helps the most disadvantaged populations.”