ACS Research News

Published on: March 5, 2026

March is Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month. See how American Cancer Society researchers are helping put an end to this disease.

Published on: March 2, 2026

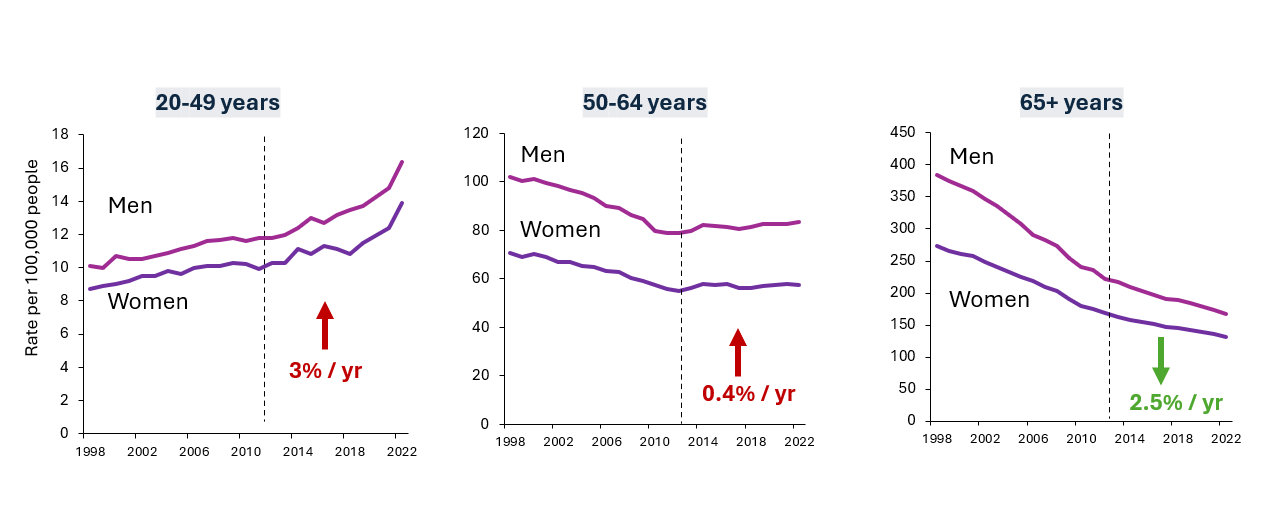

The ACS 2026 Colorectal Cancer Statistics report says CRC rates in the US are moving in two directions—up for ages <50 (esp. in the rectum) and down for 65+.

Published on: February 10, 2026

Your state can can help protect you from cancer with policies, programs, and campaigns to reduce risk factors and support cancer screening.

Published on: January 22, 2026

Awardees will receive $330,000 grants co-funded by Yosemite and the American Cancer Society to pursue critical cancer research.