Your gift is 100% tax deductible.

If Your Child Has Retinoblastoma

What is retinoblastoma?

Cancer starts when cells in the body begin to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer.

Retinoblastoma is a rare cancer of young children that starts in the retina.

The eyes start to develop well before birth. During the early stages of development, the eyes have cells called retinoblasts, which multiply to make new cells that fill the retina. At a certain point, these cells stop multiplying and become mature retinal cells.

Rarely, instead of maturing, some retinoblasts continue to grow out of control, forming retinoblastoma. Retinoblastoma tumors can be:

- Unilateral, affecting one eye

- Bilateral, affecting both eyes

- Trilateral, a condition where a child with retinoblastoma also develops a brain tumor, often near the middle of the brain in an area called the pineal gland

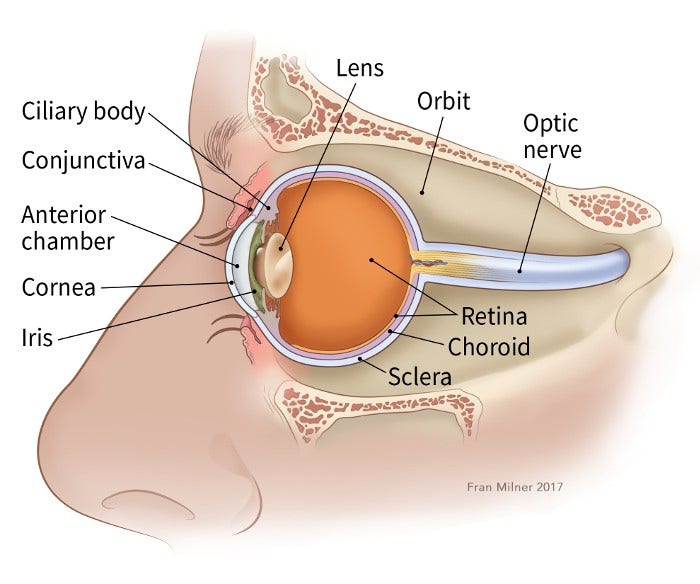

Understanding the retina

The retina is the inner layer of cells in the back of the eye. It is made up of special nerve cells that are sensitive to light. These light-sensing cells are connected to the brain by the optic nerve, which runs out of the back of the eyeball. The pattern of light (image) that reaches the retina is sent through the optic nerve to an area of the brain called the visual cortex, allowing us to see.

Why retinoblastoma forms

Retinoblastoma usually starts because of a change (mutation) in a gene called RB1. Sometimes these gene changes happen early in development or are passed on by a family member, leading to gene changes throughout all of the cells in the body (hereditary retinoblastoma), but often these gene changes occur by chance later, affecting only cells in the retina (non-heritable retinoblastoma).

Children with bilateral or trilateral retinoblastoma often have the heritable form of retinoblastoma. People with heritable retinoblastoma have a higher risk of other cancers like melanoma, a cancer of the skin, and sarcomas, cancers of the muscles or soft tissues of the body. For more information about heritable retinoblastoma, see Hereditary Retinoblastoma.

Questions to ask the doctor

- How sure are you that my child has retinoblastoma?

- Where is the tumor?

- Is there a chance it is not retinoblastoma?

- Would you please write down the kind of tumor you think my child has?

- What will happen next?

How does the doctor know my child has retinoblastoma?

Retinoblastoma is often found when it causes certain signs or symptoms.

The most common early sign of retinoblastoma is an abnormal red light reflex. Normally, if you shine a light in the eye, the pupil (the dark spot in the center of the eye) should look red because of the blood vessels in the back of the eye. But in an eye with retinoblastoma, the pupil often looks white instead (called leukocoria). This might be noticed after a flash photo is taken, or it might be noted by the child’s doctor during a routine eye exam.

Other symptoms might include:

- Changes in how the eyes look or line up with each other

- Changes in how the eyes move

- Changes in the child’s vision

Your child’s doctor might send you to an eye specialist, called an ophthalmologist, who will look at the eye more closely. These exams are often done with medicine to dilate the eyes which makes the pupil (the dark spot in the center of the eye) larger so the doctor can more easily see the retina in the back of the eye. They are also often done while a child is asleep (under anesthesia).

Imaging tests

- Ultrasound of the eye: For this test, a small ultrasound probe is placed up against the eyelid or eyeball, usually while a child is asleep. Ultrasound is a common imaging test used to confirm a child has retinoblastoma.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): OCT is like an ultrasound, but it creates detailed images of the back of the eye using light waves instead of sound waves using a hand-held tool. It can be used to help diagnose new tumors and watch for recurrent tumors that may be hard to see by visual exam due to scars on the back of the eye after treatment.

- MRI scan: MRI scans can provide very detailed images of the eye and surrounding structures, without using radiation. This test is also very good for looking at the brain and spinal cord.

- CT or CAT scan: This test uses x-rays to make detailed pictures of the inside of the body. MRI is often done instead of a CT scan in children with retinoblastoma because it does not use radiation.

- Bone scan: Most children with retinoblastoma do not need this test. But it can help show if the cancer has spread to the skull or other bones.

Biopsies

- Bone marrow biopsy: This test might be done to see if retinoblastoma has spread to the bone marrow (the soft, inner parts of some bones). A doctor uses thin, hollow needles to remove small amounts of bone marrow, usually from the hip bone. The samples are sent to a lab to check them for cancer cells.

- Liquid tumor biopsy: While sampling the tumor is discouraged in retinoblastoma, newer techniques of testing for cell-free DNA in the blood or aqueous humor (liquid in the front part of the eye) are used by some cancer centers.

Other tests

- Genetic testing: Often a blood test will be done to look for the RB1 gene change in cells outside the eye. This can help tell if a child has the heritable form of retinoblastoma, which can help doctors understand how the retinoblastoma tumor may behave and affect the type of follow-up a child needs after treatment. It might also tell doctors if other children in the family should be tested.

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap): Retinoblastoma can sometimes spread along the optic nerve, which connects the eye to the brain. If the cancer has spread to the surface of the brain, a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) can be done to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This is the fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord and can contain cancer cells. Most children with retinoblastoma do not need a lumbar puncture. If it is needed, the test is usually done while the child is asleep (under anesthesia).

For more information on these tests, see Tests for Retinoblastoma.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Who will do these tests?

- Where will they be done?

- Who can explain them to us?

- How and when will we get the results?

- Who will explain the results to us?

- What do we need to do next?

How serious is my child’s cancer?

If your child has retinoblastoma, the doctor will want to find out some key pieces of information to help decide how to treat it. The most important of these are:

- The stage of the cancer, which is based on how much cancer is within the eye and if the cancer has spread outside of the eye

- The chance of saving sight in the eye (and saving the eye itself)

- Whether the cancer is in just one eye or in both eyes

Staging systems describe how serious the cancer is and help doctors determine which treatment to use. They divide retinoblastomas into groups, based on the chance of saving the eye.

The staging of retinoblastoma can be confusing. Be sure to ask your child’s doctor if you have any questions about the stage of your child’s cancer.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Where exactly is the cancer?

- How big is the cancer?

- Can all of the cancer be removed?

- Can the vision in the eye (and the eye itself) be saved?

- Has the cancer spread anywhere else?

- What is the stage of the cancer?

- How do these things affect our treatment options?

- What will happen next?

What kind of treatment will my child need?

The treatment plan that is best for your child will depend on:

- The size and location of the tumor(s)

- How well the eye works

- Whether the cancer has extended outside the eye

- The age of the child

Many of these factors are taken into account as part of the stage of the cancer.

For unilateral retinoblastoma, or cancer in only one eye, treatment will depend on whether vision in the eye can be saved.

For bilateral retinoblastoma, where cancer affects both eyes, doctors will try to save at least one eye if possible so that the child maintains some vision.

Many children will get several types of treatment. Treatment might be needed for months or even years. No matter which types of treatment are used, it is very important that they are given by experts at centers experienced in treating these tumors.

Surgery

If the tumor has already grown large enough so that the sight in the eye cannot be saved, or if other treatments have not worked, surgery to remove the entire eye (known as enucleation) might be the best treatment option. This procedure often involves placing an implant and prosthetic eye (often made of thin plastic) that matches the healthy eye.

In cases where retinoblastoma has spread outside the eye to the orbit, a procedure called orbital exenteration, which removes the eye, optic nerve, and parts of the eye socket, may be used. This procedure is rare in the United States.

Radiation treatment

Radiation uses high-energy rays (like x-rays) to kill cancer cells. There are two types of radiation treatments that can be used to treat children with retinoblastoma:

- Brachytherapy (plaque radiotherapy): A small amount of radioactive material is placed on a plaque, shaped like a small bottle cap, and sewn surgically on the outside of the eyeball near the tumor. This is left for a few days to treat the tumor, then removed with a second surgery. This way, lower doses of focused radiation are given to the tumor, leaving other tissues unharmed.

- External beam radiation: This treatment uses radiation from a source outside of the body focused on the cancer. Most children with retinoblastoma do not need this type of radiation. It is mostly used for cancers that are not well controlled with other treatments.

Possible side effects of radiation

Side effects of brachytherapy can include damage to the retina or optic nerve, which can affect vision.

External radiation can have additional side effects on the eye and surrounding skin, such as causing cataracts (clouding of the lens, sunburn-like skin changes, and hair loss. Radiation can also affect how the bones and other structures around the eye grow, which may change how the eye looks. Ask your child’s doctor if radiation will be a part of the treatment and what to expect.

Local treatments

Retinoblastoma tumors can be treated locally with lasers and extreme temperatures to kill cancer cells. These treatments include:

- Laser photocoagulation, where a laser is focused through the pupil on blood vessels that feed the tumor to destroy them and kill the tumor

- Transpupillary thermal therapy (TTT), where a laser is focused directly on the tumor to heat and kill cancer cells

- Cryotherapy, where a probe is used to apply cold temperatures to the tumor to freeze and kill cancer cells

Children are given medications to sleep during these types of treatment. Multiple treatments may be needed over a few months to be effective. These treatments can cause damage to the retina, which can affect vision. Ask your child’s doctor if local treatments will be a part of treatment and what to expect.

Chemo

Chemotherapy (chemo) is the use of drugs to treat cancer. It might be used:

- As the first treatment, to shrink the tumor and help other treatments work better

- After other treatments, to lower the chance of the cancer coming back

- If the cancer has spread to other parts of the body

Chemo can be given systemically, throughout the entire body, when given through a vein (IV) or by mouth. In retinoblastoma, sometimes chemo may be given intraarterially (IA) directly into the ophthalmic artery that brings blood to the eye, or intravitreally, into the jelly-like substance in the eye.

Chemo that is given directly to the eye in the artery or vitreous uses much lower doses and may have side effects only to the eye or the area around the eye.

Possible side effects

Chemo given systemically can have more side effects, like:

- Hair loss

- Loss of appetite

- Diarrhea

- Nausea and vomiting

- Increased risk of infections (because of low white blood cell counts)

- Bruising and bleeding easily (from low platelet counts)

- Tiredness (caused by low red blood cell counts)

There are ways to treat most chemo side effects. If your child has side effects, talk to the cancer care team so they can help.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are research studies that test new drugs or other treatments in people. They compare standard treatments with others that may be better. Clinical trials are one way to get the newest cancer treatment. They are the best way for doctors to find better ways to treat cancer. If your doctor can find a clinical trial that might be right for your child, it is up to you whether to take part. And you can always stop at any time.

If you would like to learn more about clinical trials that might be right for your child, start by asking your doctor if your clinic or hospital conducts clinical trials. See Clinical Trials to learn more.

What about other treatments that I hear about?

When your child has retinoblastoma, you might hear about other ways to treat the cancer or its symptoms. These may not always be standard medical treatments. These treatments may be vitamins, herbs, special diets, and other things. You may wonder about these treatments.

Some of these are known to help, but many have not been tested. Some have been shown not to help. A few have even been found to be harmful. Talk to your child’s doctor about anything you are thinking about using, whether it is a vitamin, a diet, or anything else.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Do we need any other tests before we can decide on treatment?

- What treatment do you think is best for my child?

- What is the goal of this treatment? How likely is it to cure the cancer?

- Will treatment include surgery? If so, who will do the surgery?

- Will my child need other types of treatment, too?

- What will these treatments be like?

- What side effects could my child have from these treatments?

- What can we do about side effects that my child might have?

- Is there a clinical trial that might be right for my child?

- What about vitamins or special diets? Can any supplements help and are they safe?

- How soon do we need to start treatment?

- What should we do to be ready for treatment?

- Is there anything we can do to help the treatment work better?

- What is the next step?

What will happen after treatment?

You will be glad when treatment is over. But it is hard not to worry about cancer coming back. Even when cancer never comes back, people still worry about it. For years after treatment ends, your child will see their cancer doctor. Be sure they go to these follow-up visits. Your child will have exams, blood tests, and maybe other tests to see if the cancer has come back.

These doctor visits may be very frequent at first. Then, the longer your child is cancer-free, the less often the visits are needed.

Anyone with cancer, their caregivers, families, and friends, can benefit from help and support. The American Cancer Society offers the Cancer Survivors Network (CSN), a safe place to connect with others who share similar interests and experiences. We also partner with CaringBridge, a free online tool that helps people dealing with illnesses like cancer stay in touch with their friends, family members, and support network by creating their own personal page where they share their journey and health updates.

- Written by

- Words to know

Developed by the American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team with medical review and contribution by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Chemotherapy (KEY-mo-THAIR-uh-pee): The use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Also called chemo.

Iris: The colored part of the front of the eye

Metastasis (muh-TAS-tuh-sis): The spread of cancer cells from where they started to other places in the body.

Ocularist (OCK-yoo-luh-rist): A professional who creates and fits artificial

eyes

Orbit: The area around the eye

Pupil: The small hole in the middle of the iris, through which light enters the eye

Radiation (ray-dee-AY-shun) therapy: The use of high-energy rays (like x-rays) to kill cancer cells.

Retina (RET-in-uh): The inner layer of cells in the back of the eye. These are the cells in which retinoblastoma starts.

Vitreous humor (VIT-ree-us HYOO-mer): The jelly-like substance inside the eye

Last Revised: September 11, 2025

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.