Your gift is 100% tax deductible.

Chemotherapy for Bile Duct Cancer

Chemotherapy (chemo) is treatment with cancer-killing drugs that are usually given into a vein (IV) or taken by mouth. These drugs enter the bloodstream and reach all areas of the body, making this treatment useful for some cancers that have spread to organs beyond the bile duct. Because the drugs reach all the areas of the body, this is known as a systemic treatment.

How is chemotherapy used to treat bile duct cancer?

Chemo can help some people with bile duct cancer and can be used in these ways:

- After surgery: Chemo may be given after surgery (sometimes with radiation therapy) to try to lower the risk that the cancer will come back. This is called adjuvant chemo.

- Before surgery: It may be given before surgery for cancers that might be able to be completely removed. Chemo might shrink the tumor enough to improve the odds that surgery will be successful. This is called neoadjuvant treatment.

- As part of the main treatment for some advanced cancers: Chemo can be used (usually with immunotherapy) for more advanced cancers that cannot be removed or have spread to other parts of the body. Chemo does not cure these cancers, but it might help people live longer.

- As palliative therapy: Chemo can help shrink tumors or slow their growth for a time. This can help relieve symptoms from the cancer, for instance, by shrinking tumors that are pressing on nerves and causing pain.

Doctors give chemo in cycles, with each period of treatment followed by a rest period to give the body time to recover. Chemo cycles generally last about 3 to 4 weeks. Chemo usually isn't recommended for people in poor health, but advanced age by itself is not a barrier to getting chemo.

Hepatic artery infusion (HAI)

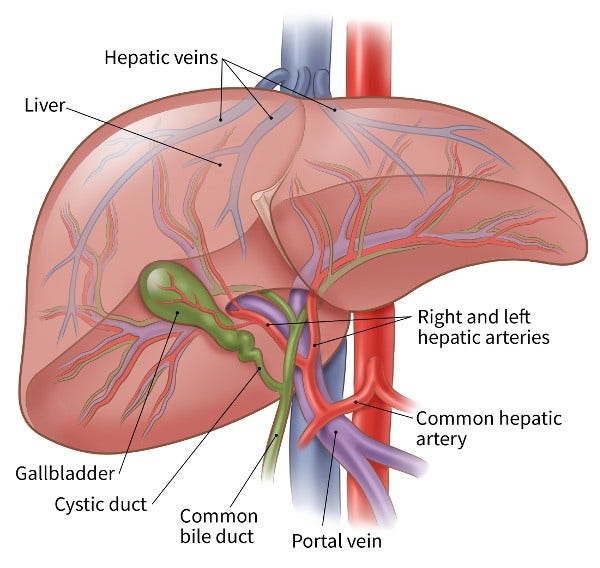

Because giving chemo into a vein (IV) isn't always helpful for bile duct cancer, doctors have tried giving the drugs right into the main artery going into the liver, called the hepatic artery. The hepatic artery also supplies most bile duct tumors, so putting the chemo into this artery means more chemo goes to the tumor. The healthy liver then removes most of the remaining drug before it can reach the rest of the body. This can lessen chemo side effects.

HAI may help some people whose cancer couldn't be removed by surgery live longer, but more research is needed. This technique often requires surgery to put a catheter into the hepatic artery, and many people with bile duct cancer are not well enough to have this surgery.

Trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE)

Embolization is a procedure where a substance is put into the blood vessels to help stop blood from getting to a tumor. TACE uses tiny beads of chemo to do this. A catheter is used to put the beads into the artery that "feeds" the tumor. The beads lodge there to block blood flow and give off the chemo. TACE may be used for tumors that can't be removed.

Drugs used to treat bile duct cancer

The drugs used most often to treat bile duct cancer include:

- Gemcitabine (Gemzar)

- Cisplatin (Platinol)

- Capecitabine (Xeloda)

- Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)

In some cases, 2 or more of these drugs may be combined to try to make them more effective. For example, combining gemcitabine and cisplatin may help people live longer than getting just gemcitabine alone.

Possible side effects of chemotherapy

Chemo drugs attack cells that are dividing quickly, which is why they work against cancer cells. But other cells in the body also divide quickly, such as those in the bone marrow (where new blood cells are made), the lining of the mouth and intestines, and the hair follicles. These cells can be affected by chemo, which can lead to side effects.

The side effects of chemo depend on the type and dose of drugs given, how they're given, and the length of treatment. Side effects can include:

- Hair loss

- Mouth sores

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Nerve damage (neuropathy) which can lead to numbness, tingling, and even pain in the hands and feet

- Increased chance of infections (from having too few white blood cells)

- Easy bruising or bleeding (from having too few blood platelets)

- Fatigue (from having too few red blood cells)

- Organ dysfunction (can affect function of the kidney and liver)

Ask your cancer care team what you should watch for. Most side effects are short-term and go away after treatment ends. There are often ways to lessen these side effects. For example, drugs can be given to help prevent or reduce nausea and vomiting. Be sure to ask your cancer care team about medicines to help reduce side effects.

Tell your cancer care team about any side effects you notice, so they can be treated right away. Most side effects can be treated. In some cases, the doses of the chemo drugs can be reduced or treatment can be delayed or stopped to keep the side effects from worsening.

More information about chemotherapy

For more general information about how chemotherapy is used to treat cancer, see Chemotherapy.

To learn about some of the side effects listed here and how to manage them, see Managing Cancer-related Side Effects.

- Written by

- References

Developed by the American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team with medical review and contribution by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Abou-Alfa GK, Jarnagin W, Lowery M, D’Angelica M, Brown K, Ludwig E, Covey A, Kemeny N, Goodman KA, Shia J, O’Reilly EM. Liver and bile duct cancer. In: Neiderhuber JE, Armitage JO, Doroshow JH, Kastan MB, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff’s Clinical Oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA. Elsevier; 2014:1373-1395.

Kelley RK, Bridgewater J, Gores GJ, Zhu AX. Systemic therapies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020 Feb;72(2):353-363. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.009. PMID: 31954497.

Moris D, Palta M, Kim C, Allen PJ, Morse MA, Lidsky ME. Advances in the treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: An overview of the current and future therapeutic landscape for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023 Mar;73(2):198-222. doi: 10.3322/caac.21759. Epub 2022 Oct 19. PMID: 36260350.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), Biliary Tract Cancers, Version 2.2024 -- April 19, 2024. Accessed at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/btc.pdf on May 20, 2024.

Patel T, Borad MJ. Carcinoma of the biliary tree. In: DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, eds. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg’s Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015:715-735.

Last Revised: October 11, 2024

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.