Your gift is 100% tax deductible.

Signs and Symptoms of Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors

Most gastrointestinal (GI) neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) grow slowly. If they do cause symptoms, the symptoms tend to be vague. When trying to figure out what’s going on, other, more common possible causes are likely to be explored first. This can delay a diagnosis, sometimes even for several years. But some NETs do cause symptoms that lead to their diagnosis.

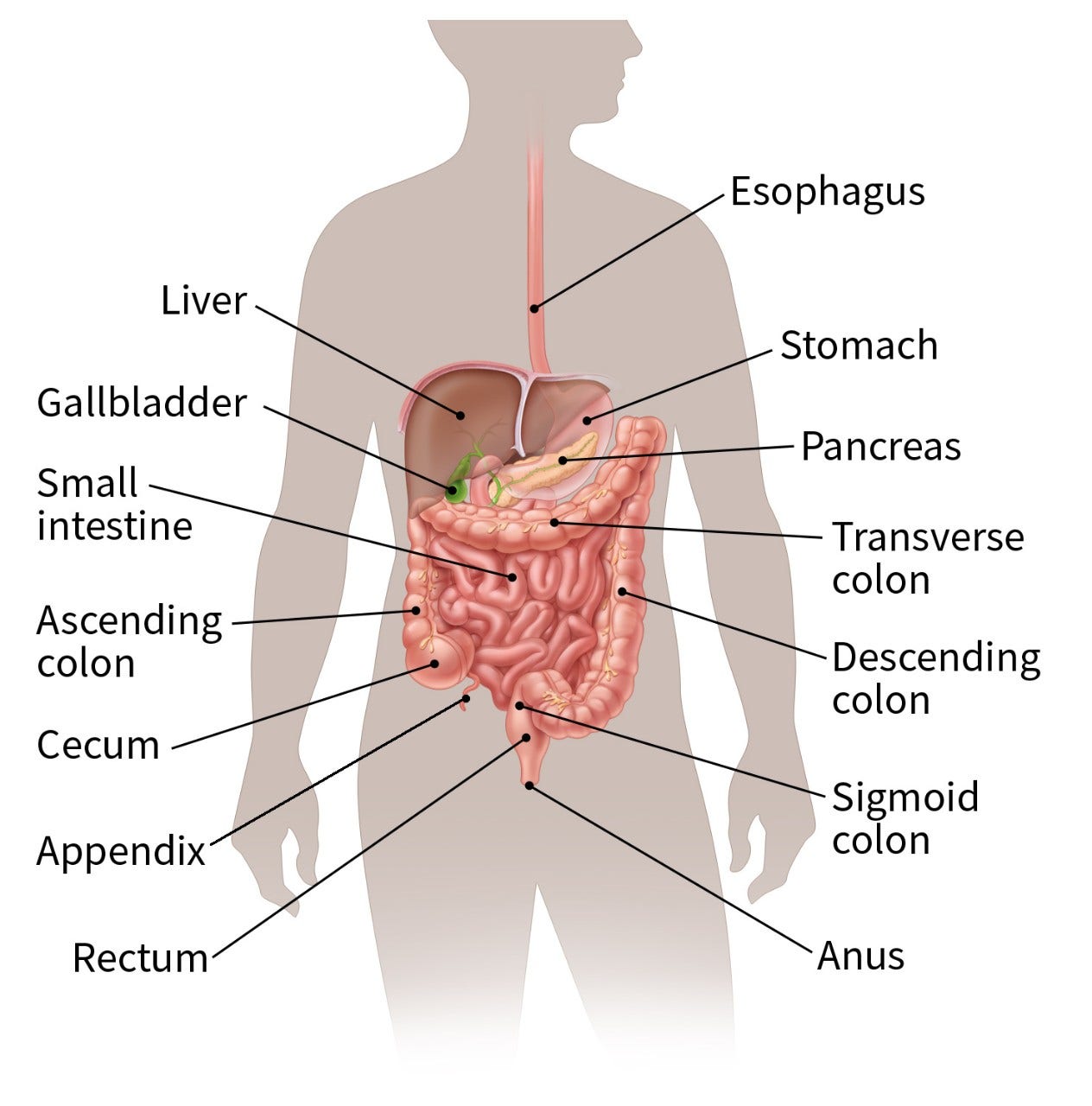

Symptoms by tumor location

The symptoms a person can have from a GI neuroendocrine tumor often depend on where it is growing.

The appendix

People with tumors in their appendix often don’t have symptoms. If the cancer is discovered, it is usually when the appendix is removed for some other problem. Sometimes, the tumor blocks the opening between the appendix and the rest of the intestine and causes appendicitis. This leads to symptoms like fever, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal (belly) pain.

The small intestine or colon

If the tumor starts in the small intestine, it can cause the intestines to kink and be blocked for a while. This can cause cramps, belly pain, weight loss, fatigue, bloating, diarrhea, or nausea and vomiting, which might come and go. These symptoms can sometimes go on for years before the neuroendocrine tumor is found. A tumor usually can grow fairly large before it completely blocks (obstructs) the intestine and causes severe belly pain, nausea, and vomiting, and a potentially life-threatening situation.

Sometimes a neuroendocrine tumor can block the opening of the ampulla of Vater, which is where the common bile duct (from the liver) and the pancreatic duct (from the pancreas) empty into the intestine. When this is blocked, bile can back up, leading to yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice). Pancreatic juices can also back up, leading to an inflamed pancreas (pancreatitis), which can cause belly pain, nausea, and vomiting.

A neuroendocrine tumor sometimes can cause intestinal bleeding. This can lead to anemia (too few red blood cells) with fatigue and shortness of breath.

The rectum

Rectal neuroendocrine tumors are often found during routine exams, even though they can cause pain, rectal bleeding, and constipation.

The stomach

Neuroendocrine tumors that develop in the stomach usually grow slowly and often do not cause symptoms. They are sometimes found when the stomach is examined by an endoscopy looking for other things. Some can cause symptoms such as the carcinoid syndrome (see below).

Signs and symptoms from hormones made by neuroendocrine tumors

Some neuroendocrine tumors release hormones into the bloodstream. This can cause different symptoms depending on the hormones released.

Carcinoid syndrome

About 1 out of 10 carcinoid tumors release enough hormone-like substances into the bloodstream to cause carcinoid syndrome symptoms. These include:

- Facial flushing (redness and warm feeling)

- Severe diarrhea

- Wheezing

- Fast heartbeat

Many people find that factors such as stress, heavy exercise, and drinking alcohol trigger these symptoms. Over time, these hormone-like substances can damage heart valves, causing shortness of breath, weakness, and a heart murmur (an abnormal heart sound).

Not all GI neuroendocrine tumors cause the carcinoid syndrome. For example, those in the rectum usually do not make the hormone-like substances that cause these symptoms.

Most cases of carcinoid syndrome occur only after the cancer has already spread to other parts of the body. Neuroendocrine tumors in the midgut (appendix, small intestine, cecum, and ascending colon) that spread to the liver are most likely to cause carcinoid syndrome.

Carcinoid crisis

Carcinoid crisis is a life-threatening reaction in people with GI neuroendocrine tumors. This is usually triggered by extreme stress, such as surgery. It causes changes in blood pressure and heart rate. It is the most serious complication of carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid crisis may be prevented and successfully treated with octreotide, which is usually given in a vein (IV) before a medical procedure or surgery.

Cushing syndrome

Some neuroendocrine tumors produce ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone), a substance that causes the adrenal glands to make too much cortisol (a steroid). This can cause Cushing syndrome, with symptoms of:

- Weight gain

- Muscle weakness

- High blood sugar (even diabetes)

- High blood pressure

- Increased body and facial hair

- A bulge of fat on the back of the neck

- Skin changes like stretch marks (called striae)

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

Neuroendocrine tumors can make a hormone called gastrin that signals the stomach to make acid. Too much gastrin can cause Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, in which the stomach makes too much acid. High acid levels can irritate the stomach lining and even lead to stomach ulcers, which can cause pain, nausea, and loss of appetite.

Severe ulcers can bleed. If the bleeding is mild, it can lead to anemia (too few red blood cells), causing symptoms like feeling tired and being short of breath. If the bleeding is more severe, it can make stools black and tarry. Severe bleeding can be life-threatening.

If stomach acid reaches the small intestine, it can damage the intestinal lining and break down digestive enzymes before they have a chance to digest food. This can cause diarrhea and weight loss.

- Written by

- References

Developed by the American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team with medical review and contribution by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

National Cancer Institute Physician Data Query (PDQ). Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. 2024. Accessed https://www.cancer.gov/types/gi-carcinoid-tumors/hp/gi-carcinoid-treatment-pdq#section/_21 on March 20, 2025.

Norton JA and Kunz PL. Carcinoid) Tumors and the Carcinoid Syndrome. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015:1218-1226.

Pandit S, Annamaraju P, Bhusal K. Carcinoid Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Feb 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448096/

Schneider DF, Mazeh H, Lubner SJ, Jaume JC, Chen H. Cancer of the Endocrine System. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Doroshow JH, Kastan MB, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2014:1112-1142.

Last Revised: August 8, 2025

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.