Your gift is 100% tax deductible

If You Have a Lung Carcinoid Tumor

If you or someone you know has just been diagnosed with a lung carcinoid tumor, this short guide can help. Find information on lung carcinoid tumors here.

What is a lung carcinoid tumor?

Lung carcinoid tumors (also known as lung carcinoids) are a type of lung cancer. Cancer starts when cells begin to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer, and can spread to other areas. (To learn more about how cancers start and spread, see What Is Cancer?)

Lung carcinoid tumors are not common and tend to grow slower than other types of lung cancers.

Where do lung carcinoid tumors start?

Lung carcinoid tumors start in neuroendocrine cells, a special kind of cell found in the lungs. These cells make hormones that help the lungs control air flow and blood flow. They may also help control the growth of other cells in the lungs.

Neuroendocrine cells are part of a system called the neuroendocrine system. They are also found in other areas of the body, but only cancers that form from neuroendocrine cells in the lungs are called lung carcinoid tumors.

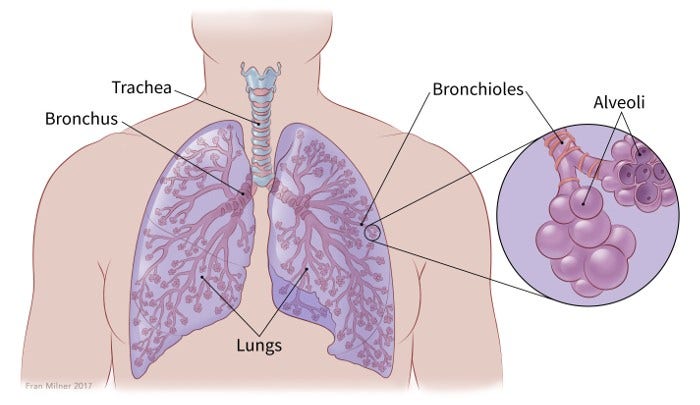

The lungs

The lungs are 2 sponge-like organs found in the chest. The right lung has 3 parts, called lobes. The left lung has 2 lobes. The left lung is smaller because the heart takes up more room on that side of the body. The lungs bring air in and push it out of the body. They take in oxygen and get rid of carbon dioxide, a waste product.

The windpipe, or trachea, brings air down into the lungs. It splits into 2 tubes (large airways) called bronchi. (Just 1 is called a bronchus.) The bronchioles are smaller airways that branch off from the bronchi.

Ask your doctor to show you on this picture where your cancer is found.

Depending on where your tumor is, you might have different symptoms and might have different treatment options. Sometimes doctors name tumors based on where they are located in the lungs:

- Most carcinoid tumors form in the walls of large airways (bronchi) near the center of the lungs. These are called central carcinoids.

- When carcinoid tumors are found in the smaller airways (bronchioles) toward the outer edges of the lungs, they're called peripheral carcinoids.

Are there different kinds of lung carcinoid tumors?

There are two types of lung carcinoid tumors:

- Typical carcinoids tend to grow slowly and rarely spread beyond the lungs. They also do not seem to be linked with smoking.

- Atypical carcinoids grow a little faster and are somewhat more likely to spread to other organs. They are much less common than typical carcinoids and may be found more often in people who smoke.

There are also other types of lung cancer that are more common than lung carcinoid tumors. See Lung Cancer to learn more.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Why do you think I might have a lung carcinoid tumor?

- Could my symptoms be caused by something else?

- Would you please write down the kind of cancer you think I might have?

- What will happen next?

How will the doctor know if I have a lung carcinoid tumor?

Symptoms of lung carcinoid tumors are cough, chest pain, and trouble breathing. The doctor will ask you about your health and do a physical exam.

If signs point to a lung carcinoid tumor, more tests will be done. Here are some of the tests you may need:

Chest x-ray: This is often the first test used to look for spots on your lungs. If a change is seen, you will need more tests.

CT scan: This is also called a “CAT scan.” A CT scan is a special kind of x-ray that takes pictures of your insides. CT scans are sometimes used when doing a biopsy (see below).

PET scan: Before this test, a special radioactive material is put into a vein with an IV. This substance travels through your blood and is attracted to areas of cancer. Then, pictures of your insides are taken with a special camera. If there is cancer, the material shows up as “hot spots” where the cancer is found. This test is useful when your doctor thinks the cancer has spread, but doesn’t know where.

Octreotide scan: This test is like a PET scan, but the radioactive material is attached to a drug called octreotide that's attracted to carcinoid tumors.

Biopsy: For a biopsy, the doctor takes out a small piece of the lung tumor. It’s sent to the lab to see if there are cancer cells in it. This is the best way to know for sure if you have cancer.

Bronchoscopy: A thin, lighted, bendable tube is passed through your mouth into the bronchi. The doctor can look through the tube to find tumors. The tube also can be used to take out a piece of the tumor or fluid to see if there are cancer cells. You may be given drugs to make you sleep for this test.

Blood and urine tests: Blood and urine tests are not used to find lung cancer, but they can help tell the doctor more about your health, which helps plan your treatment.

Questions to ask the doctor

- What tests will I need to have?

- Who will do these tests?

- Where will they be done?

- Who can explain them to me?

- How and when will I get the results?

- Who will explain the results to me?

- What do I need to do next?

How serious is my cancer?

If you have a lung carcinoid tumor, the doctor will want to find out how far it has spread. This is called staging. Knowing the stage of the cancer helps your doctor decide what treatment is best for you.

Your doctor might give you a number stage for your cancer, between 1 and 4. Cancers with higher numbers have spread more than cancers with lower numbers. But most doctors decide treatment based on whether the tumor can be removed with surgery or not:

- If your cancer is resectable (able to be removed with surgery), you most likely will get surgery to try to cure the cancer.

- If your cancer is not resectable (not able to be removed with surgery), it will be harder to treat. You might still have some kind of surgery, but if that is not a good option, your doctor might recommend chemotherapy or radiation.

Be sure to ask your doctor about the stage of your cancer and what it might mean for you.

Questions to ask the doctor

- Do you know the stage of the cancer?

- If not, how and when will you find out the stage of the cancer?

- Would you explain to me what the stage means in my case?

- Based on the stage of the cancer, how long do you think I’ll live?

- Can my cancer be removed with surgery? Is surgery an option to treat my cancer?

- What will happen next?

What kind of treatment will I need?

The treatment plan that is best for you depends on the stage of your cancer, your age and overall health, the possibility the cancer can be removed completely with surgery, and other factors. Treatment options include:

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy or radioactive drugs

- Chemotherapy or other drugs

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for lung carcinoid tumors whenever possible. If the tumor hasn’t spread, it can often be cured by just doing surgery.

Types of lung surgery

Different types of surgery (also called operations) can be used to treat and possibly cure lung carcinoid tumors. These operations require general anesthesia (where you are in a deep sleep) and are usually done through a surgical cut between the ribs in the side of the chest (called a thoracotomy).

- Pneumonectomy: An entire lung is removed.

- Lobectomy: An entire section (lobe) of a lung is removed.

- Segmentectomy or wedge resection: Part of a lobe is removed.

Checking lymph nodes during surgery

Lymph nodes are small glands that are part of your immune system. If cancer has spread, it often goes to the lymph nodes first. During your surgery, lymph nodes near the lungs are usually removed to see if the cancer has spread. This can also help the doctor find out if the cancer is likely to come back after treatment.

Side effects of surgery

Different types of surgery have different risks and side effects, so talk to your doctor about what to expect. Some possible side effects include bleeding, infections, and pneumonia.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays (such as x-rays) to kill cancer cells. Your doctor might recommend radiation therapy if you're not able to have surgery. It may also be given after surgery in some cases if there’s a chance some of the tumor was not removed. Radiation can also be used to help with symptoms caused by the tumor, such as pain, bleeding, or trouble swallowing. Getting radiation is a lot like getting an x-ray. It’s given in small doses every day for many weeks.

Side effects of radiation therapy

If your doctor suggests radiation as your treatment, ask about what side effects might happen. The most common side effects of radiation are:

- Skin changes where the radiation is given

- Feeling very tired (fatigue)

Most side effects get better after treatment ends. Some might last longer. Talk to your doctor about what you can expect.

Radioactive drugs

Radioactive drugs are another kind of radiation therapy. These are drugs that combine radioactive material with another substance that's attracted to lung carcinoid tumors. This lets doctors deliver high doses of radiation directly to the tumors. Radioactive drugs are put into your blood with an IV, like getting chemo. The most common side effects are nausea, kidney and liver problems, low white blood counts, low platelet counts, and vomiting.

Chemo

Chemo is the short word for chemotherapy – the use of drugs to fight cancer. Most carcinoid tumors are not treated with chemo, but sometimes it's helpful if the tumors have spread or are causing severe symptoms. It's also used if other treatments aren't working, or for tumors that are growing fast. Some people who get surgery as their main treatment may need chemo after.

The drugs may be given through a needle into a vein or taken as pills. These drugs go into the blood and spread through the body.

Chemo is given in cycles or rounds. There’s often a rest period as part of each cycle of treatment. This gives the body time to recover. Chemo drugs can be used together or alone, and often along with other types of drugs. Treatment often lasts for many months.

Side effects of chemo

Chemo can have many side effects, like:

- Hair loss

- Mouth sores

- Not feeling like eating

- Diarrhea

- Feeling sick to your stomach and throwing up

- More risk of infections

- Bruising and bleeding easily

- Tiredness

But these problems tend to go away after treatment ends. There are ways to treat most chemo side effects. Be sure to talk to your cancer care team so they can help.

Other drugs

People with lung carcinoid tumors that have spread might be treated with other kinds of drugs.

One drug, everolimus (Afinitor®) is sometimes used to treat lung carcinoid tumors when chemo doesn't work. Getting this drug is a lot like getting chemo, but it works differently. It's called a targeted therapy drug because it targets specific parts of cancer cells. Side effects can include diarrhea, feeling very tired (fatigue), rash, mouth sores, and swelling in your legs or arms.

Other drugs, like octreotide and lanreotide, can sometimes slow the growth of lung carcinoid tumors or help with symptoms. These drugs are given as injections (shots) under the skin.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are research studies that test new drugs or other treatments in people. They compare standard treatments with others that may be better.

Clinical trials are one way to the newest cancer treatment. They are the best way for doctors to find better ways to treat cancer. If your doctor can find one that’s studying the kind of cancer you have, it’s up to you whether to take part. And if you do sign up for a clinical trial, you can always stop at any time.

If you would like to learn more about clinical trials that might be right for you, start by asking your doctor if your clinic or hospital conducts clinical trials. See Clinical Trials to learn more.

What about other treatments that I hear about?

When you have cancer you might hear about other ways to treat your cancer or treat your symptoms. These may not always be standard medical treatments. These treatments may be vitamins, herbs, diets, and other things. You may wonder about these treatments.

Some of these are known to help, but many have not been tested. Some have been shown not to be helpful. A few have even been found to be harmful. Talk to your doctor about anything you are thinking about using, whether it’s a vitamin, a diet, or anything else.

Questions to ask the doctor

- What treatment do you think is best fo me?

- What is the goal of this treatment? Do you think it could cure the cancer?

- Will treatment include surgery? If so, what will the surgery be like?

- Will I need other types of treatment, too?

- What’s the goal of these treatments?

- What side effects could I have from these treatments?

- What can I do about side effects that I might have?

- Is there a clinical trial that might be right for me?

- What about vitamins or diets that friends tell me about? How will I know if they are safe?

- How soon do I need to start treatment?

- What should I do to be ready for treatment?

- Is there anything I can do to help the treatment work better?

- What’s the next step?

What will happen after treatment?

You’ll be glad when treatment is over. But it’s hard not to worry about cancer coming back. Even when cancer never comes back, people still worry about this.

For years after treatment ends, you will see your cancer doctor. Be sure to go to all of these follow-up visits. You will have exams, blood tests, and maybe other tests, like CT scans or octreotide scans, to tell if the cancer has come back.

For the first year after treatment, your visits may be every 3 months. You may have CT scans and blood tests. After the first year or so, your visits might be every 6 months, and then at least once a year after 5 years.

Having cancer and dealing with treatment can be hard, but it can also be a time to look at your life in new ways. You might be thinking about how to improve your health. Call us at 1-800-227-2345 or talk to your cancer care team to find out what you can do to feel better.

You can’t change the fact that you have cancer. What you can change is how you live the rest of your life – making healthy choices and feeling as well as you can.

Anyone with cancer, their caregivers, families, and friends, can benefit from help and support. The American Cancer Society offers the Cancer Survivors Network (CSN), a safe place to connect with others who share similar interests and experiences. We also partner with CaringBridge, a free online tool that helps people dealing with illnesses like cancer stay in touch with their friends, family members, and support network by creating their own personal page where they share their journey and health updates.

- Written by

- Words to know

- How can I learn more?

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

Biopsy (BY-op-see): taking out a piece of tissue to see if there are cancer cells in it

Bronchoscopy (brong-KOS-kuh-pee): use of a thin, lighted, flexible tube that’s passed through the mouth into the bronchi of the lungs. The doctor can look through the tube to find tumors or to take out a piece of tumor or fluids to test for cancer cells.

Bronchus (BRONG-kus) plural bronchi (BRONG-ki): in the lungs, the 2 main air passages leading from the windpipe or trachea. The bronchi are the tubes that allow air to move in and out of the lungs.

Metastasis (muh-TAS-tuh-sis): cancer cells that have spread from where they started to other places in the body

Trachea (TRAY-key-uh): the windpipe, or the main passage for air coming from the nose and mouth into the bronchi and lungs

We have a lot more information for you. You can find it online at www.cancer.org. Or, you can call our toll-free number at 1-800-227-2345 to talk to one of our cancer information specialists.

Last Revised: August 28, 2018

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.