Your gift is 100% tax deductible.

What Is Kidney Cancer?

Kidney cancer is a type of cancer that starts in the kidney when cells in the body begin to grow out of control. As more cancer cells develop, they can form a tumor and, with time, might spread to other parts of the body.

The kidneys

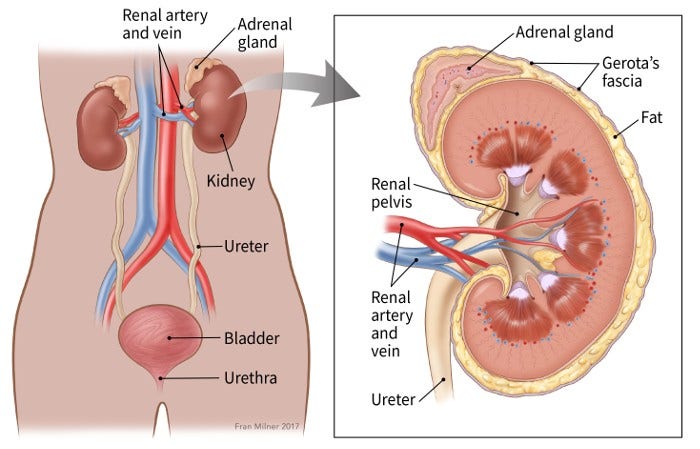

The kidneys are a pair of bean-shaped organs, each about the size of a fist. They are attached to the upper back wall of the abdomen and are protected by the lower rib cage. One kidney is just to the left and the other just to the right of the backbone.

An adrenal gland sits on top of each kidney. Each kidney and adrenal gland are surrounded by fat and a thin, fibrous layer known as Gerota’s fascia.

The kidneys’ main job is to remove excess water, salt, and waste products from blood coming in from the renal arteries. These substances become urine. Urine collects in the center of each kidney in an area called the renal pelvis and then leaves the kidneys through long slender tubes called ureters. The ureters lead to the bladder, where the urine is stored until you urinate.

The kidneys also have other jobs:

- They make a hormone called renin that helps control blood pressure.

- They help make sure the body has enough red blood cells by making a hormone called erythropoietin. This hormone tells the bone marrow to make more red blood cells.

Our kidneys are important, but our bodies can function with only one kidney. Many people in the United States are living normal, healthy lives with just one kidney.

Some people do not have working kidneys at all, and live with the help of a medical procedure called dialysis. The most common form of dialysis uses a specially designed machine that filters blood much like a real kidney would.

Types of kidney cancer

Not all cancers that start in the kidneys are the same. Different types of kidney cancer can act differently and might need different treatments.

Renal cell carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC), also known as renal cell cancer, is the most common type of kidney cancer. About 9 out of 10 kidney cancers are renal cell carcinomas. If you’re told you have kidney cancer, it’s most likely to be a renal cell carcinoma.

Although RCC usually grows as a single tumor within a kidney, sometimes a person can have more than one tumor in a kidney or even tumors in both kidneys at the same time.

There are several subtypes of RCC. Knowing the subtype of RCC can help decide on treatment and can also help your doctor figure out if your cancer might be caused by an inherited genetic syndrome. See Risk Factors for Kidney Cancer for more information about inherited kidney cancer syndromes.

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma

This is the most common form of RCC. About 7 out of 10 people with RCC have this kind of cancer. When seen with a microscope, the cells that make up clear cell RCC look very pale or clear.

Non-clear cell renal cell carcinomas

These include all subtypes that are not clear cell RCCs.

Papillary renal cell carcinoma: About 1 in 10 RCCs are of this type. These cancers form little finger-like projections (called papillae) in some, if not most, of the tumor. Some doctors call these cancers chromophilic because the cells take in certain dyes and look pink when seen with a microscope.

Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: This subtype accounts for about 5% (5 cases in 100) of RCCs. The cells of these cancers are pale, like the clear cells, but are darker and have certain other features that can be recognized when looked at very closely.

Rare subtypes of renal cell carcinoma: Several other subtypes each make up less than 1% of RCCs. These include:

- Collecting duct RCC

- Multilocular cystic RCC

- Medullary carcinoma (renal medullary carcinoma)

- Mucinous tubular and spindle cell carcinoma

- Neuroblastoma-associated RCC

There are some other rare subtypes as well, which have certain gene or chromosome changes inside the cancer cells.

Unclassified renal cell carcinoma: Some RCCs are labeled as ‘unclassified’ because the way they look doesn’t fit into any of the other categories or because there is more than one type of cancer cell present. These account for about 5% of RCCs.

Other types of kidney cancers

Other types of kidney cancers include transitional cell carcinomas, Wilms tumors, and renal sarcomas.

Transitional cell carcinoma

Of every 100 cancers in the kidney, about 5 to 10 are transitional cell carcinomas (TCCs), also known as urothelial carcinomas.

Transitional cell carcinomas start in the lining of the renal pelvis (where the ureters meet the kidneys). This lining is made up of cells called transitional cells, which are the same cells that line the ureters and bladder. Cancers that develop from these cells look like other urothelial carcinomas, such as bladder cancer, when looked at closely. Like bladder cancer, these cancers are often linked to cigarette smoking and being exposed to certain cancer-causing chemicals in the workplace.

People with TCC often have the same signs and symptoms as people with renal cell cancer − blood in the urine and, sometimes, back pain. For more information about transitional cell carcinoma, see Bladder Cancer.

Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma)

Wilms tumors almost always occur in children. This type of cancer is very rare in adults. To learn more about this type of cancer, see Wilms Tumor.

Renal sarcoma

Renal sarcomas are a rare type of kidney cancer that begin in the blood vessels or connective tissue of the kidney. They make up less than 1% of all kidney cancers. Sarcomas are discussed in more detail in Sarcoma- Adult Soft Tissue Cancer.

Benign (non-cancerous) kidney tumors

Some kidney tumors are benign (not cancer). They don’t metastasize (spread) to other parts of the body, although they can still grow and cause problems.

Benign kidney tumors can usually be treated, if needed, by removing or destroying them. This can be done with many of the same treatments that are also used for kidney cancers, such as surgery or radiofrequency ablation (RFA). The choice of treatment depends on many factors, such as the size of the tumor and if it is causing symptoms, the number of tumors, if there are tumors in both kidneys, and a person’s general health.

Angiomyolipoma

Angiomyolipomas are the most common type of benign kidney tumor. They are seen more often in women. They can develop sporadically or in people with tuberous sclerosis, a genetic condition that also affects the heart, eyes, brain, lungs, and skin.

These tumors are made up of different types of connective tissues (blood vessels, smooth muscles, and fat). If they aren’t causing any symptoms, they can often just be watched closely. If they start causing problems (like pain or bleeding), they may need to be treated.

Oncocytoma

Oncocytomas are uncommon benign kidney tumors that can sometimes grow quite large. They are seen more often in men, and do not normally spread to other organs. Surgery often cures them.

The rest of our information about kidney cancer focuses on renal cell carcinoma and not on less common types of kidney tumors.

- Written by

- References

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Our team is made up of doctors and oncology certified nurses with deep knowledge of cancer care as well as editors and translators with extensive experience in medical writing.

Atkins MB, Bakouny Z, Choueiri TK. Epidemiology, pathology, and pathogenesis of renal cell carcinoma. UpToDate. 2023. Accessed at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-pathology-and-pathogenesis-of-renal-cell-carcinoma on December 5, 2023.

Gupta S, Richie JP. Malignancies of the renal pelvis and ureter. UpToDate. 2023. Accessed at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/malignancies-of-the-renal-pelvis-and-ureter on December 5, 2023.

Kay FU, Pedrosa I. Imaging of solid renal masses. Urol Clin North Am. 2018; 45:311-330. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2018.03.013. Epub 2018 Jun 15.

McNamara MA, Zhang T, Harrison MR, George DJ. Ch 79: Cancer of the kidney. In: Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Doroshow JH, Kastan MB, Tepper JE, eds. Abeloff’s Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier: 2020.

Torres VE, Pei Y. Renal angiomyolipomas (AMLs): Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate. 2023. Accessed at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/renal-angiomyolipomas-amls-epidemiology-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis on December 5, 2023.

Last Revised: May 1, 2024

American Cancer Society medical information is copyrighted material. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.

American Cancer Society Emails

Sign up to stay up-to-date with news, valuable information, and ways to get involved with the American Cancer Society.