Incidence Drops for Cervical Cancer But Rises for Prostate Cancer

Latest data shows improvements for cervical cancer are linked to HPV vaccine and downturns in prostate cancer are driven by advanced-stage disease.

Significant changes in cancer prevention and screening in the United States in recent years helped lead to both promising and worrisome 2023 cancer statistics reported by the American Cancer Society (ACS). In good news, data from women ages 20 to 24 who were first to receive the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine showed a 65% reduction in cervical cancer incidence rates from 2012 through 2019. In contrast, data after several years of shifts in screening guidelines about the use of prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing showed a 3% increase in prostate cancer incidence rate each year from 2014 through 2019, about 99,000 new cases. This is the first increase in about 20 years.

In general, though, incidence rates improved less for women than for men during these years. Lung cancer decreased about half as fast in women as in men. Liver cancer and melanoma incidence rates both increased in women, while they declined in men younger than 50 and stabilized in older men. Women also saw increases in the incidence of breast cancer and endometrial (uterine corpus) cancer.

In Plain Words

Want to know what incidence rate or death rate means? Or who’s included in AIAN and Hispanic groups? See Understanding Cancer Research Terms.

Although the risk of dying from cancer in the US has continually decreased over the past 29 years, these increases in breast, prostate, and endometrial cancers may slow future progress. All of these cancers also happen to have wide disparities in death rates based on race.

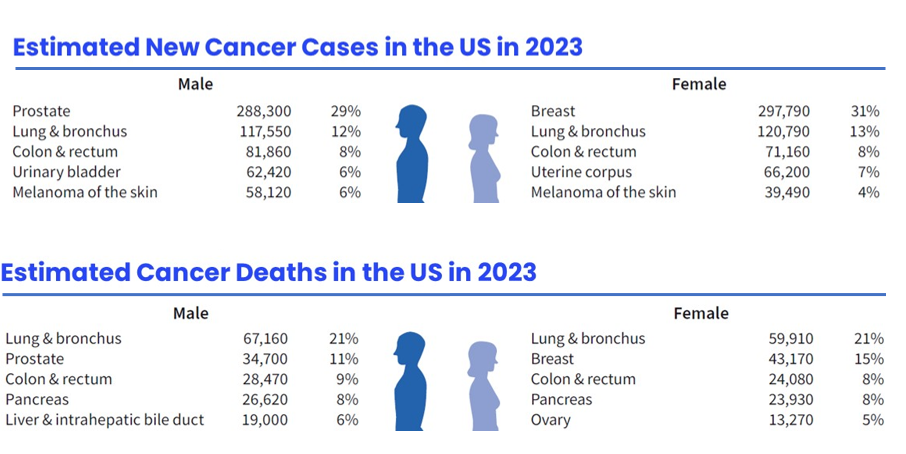

Cancer continues to be the second most common cause of death in the US, after heart disease. In the US in 2023, a total of 1.9 million new cancer cases (about 5,370 cases each day) and 609,820 deaths from cancer are expected to occur (about 1,670 deaths a day).

These estimated numbers of new cancer cases and deaths expected in the US this year are from “Cancer Statistics, 2023” in the American Cancer Society’s journal CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. The estimates are some of the most widely quoted cancer statistics in the world. The information is also available in a companion PDF report, Cancer Facts & Figures 2023 and is available on the interactive website, the Cancer Statistics Center.

HPV vaccination has the potential to virtually eliminate cervical cancer.

In 2006, females ages 9 to 26 started receiving the HPV vaccine for the first time. It protects against the strains of HPV that cause the majority of cervical cancers (HPV-16 and HPV-18). That means the first adolescents who were vaccinated are now in their 20s.

Although incidence rates were already declining because of screening, the HPV vaccine accelerated this progress. Among women ages 20 to 24, cervical cancer incidence rates declined by a total of 33% from 2005-2012 and by 65% from 2012 through 2019.

“The large drop in cervical cancer incidence is extremely exciting because this is the first group of women to receive the HPV vaccine, and it probably foreshadows steep reductions in other HPV-associated cancers,” said Rebecca Siegel, senior scientific director, surveillance research at the American Cancer Society, and the lead author of the report.

Other US studies have shown "surprisingly large" herd immunity, the study authors said. Sexually active females age 14 to 24 who were vaccinated showed a 90% reduction in infections with HPV-16 or HPV-18, and even those who had not been vaccinated had a 74% reduction in infections.

“Herd immunity occurs when even people who have not been vaccinated are protected from disease because the prevalence of the infection has been reduced by those who are vaccinated. As the number of those who are immune increases, the spread of the disease from person to person is less likely, which helps protect everyone, even those who were not vaccinated,” said Siegel.

Although HPV vaccination can “virtually eliminate cervical cancer,” the authors state, there are large differences in the proportion of people who are vaccinated between states. In 2020, only 32% of boys and girls ages 13 to 17 in Mississippi were up to date with HPV vaccination and only 43% in West Virginia. States with high proportions of vaccinated teens include Massachusetts (73%), Hawaii (74%), and Rhode Island (83%). In the coming years, these differences will become apparent in incidence rates for cervical and other HPV-associated cancers.

Differences in the initiatives to improve health, such as Medicaid expansion, may also contribute to future geographic disparities.

After about 20 years of declining incidence, the first increase in prostate cancer—especially in late-stage diagnoses—likely results from changes to PSA screening guidelines.

Screening men for prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels in a blood sample has its benefits. It helps find cancer when it is only in the prostate (localized), where it may require less intensive treatment that’s more successful at completely removing the cancer. Its use also helped decrease the risk of dying from prostate cancer by 53% from 1993 through 2020.

But PSA screening also has its risks. It can lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancers that aren’t dangerous. That’s why in 2008 the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) changed their screening guidelines to recommend against routine screening with PSA testing for men age 75 and older, and 4 years later recommended against screening for all men.

Fewer men getting screened led to rapid declines in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. That didn’t mean the cancer didn’t exist, it meant that without the use of PSA testing, cancers weren’t being found at an early stage when they are less complicated to treat and more likely to be cured. As a result, the proportion of prostate cancers diagnosed at a distant stage has more than doubled over the past 10 years. Late-stage prostate cancers are harder to treat and cure.

In an effort to regain the benefits of screening for prostate cancer, the ACS Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection advise doctors to talk with their male patients who have average risk for developing prostate cancer at age 50 to help them make an informed decision about getting tested for PSA levels. There is also more targeted screening now through the use of molecular markers and imaging to try to reduce the detection of cancers that will never cause harm. These discussions are recommended at age 45 for men with African ancestry or a family history of the cancer or cancers caused by BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, and others who have a high risk for developing prostate cancer. The conversations are recommended to start at age 40 for men who have a father or more than one brother (known as first-degree relatives) who had prostate cancer, as well as others who have at an even higher risk.

Cancer death rate continues to drop.

From its peak in 1991, the cancer death rate for men and women combined fell 33% by 2020, the most recent year for which data were available. This reduction in deaths from cancer has averted an estimated 3.8 million deaths (2.6 million in men and 1.2 million in women).

This success is largely because of fewer people smoking, which resulted in declines in lung and other smoking-related cancers. Other factors that contributed to the reduced death rate include:

- Prevention and/or early detection through screening for some cancers, including cancer in the breast, cervix, colon and rectum, and prostate

- Improved treatment, such as adjuvant chemotherapies for breast and colon cancer

- Advances in the development of targeted treatment and immunotherapy have accelerated progress in lung cancer death rates—well beyond reductions in incidence. These treatments have also decreased death rates from leukemia, melanoma, and kidney cancer.

Cancer racial disparities continue.

Racial disparities in cancer occurrence and outcomes are largely due to longstanding inequalities in wealth that affect a person’s exposure to risk factors and their access to equitable cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment. Most inequities in wealth, education, and overall standard of living among people of color stem from historical and persistent structural racism, including segregationist and discriminatory policies in criminal justice, housing, education, employment, and healthcare.

Overall cancer incidence is highest among White people, followed closely by American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) and Black people. Sex-specific incidence is highest in Black men. Incidence rates for Black men are 5% higher than White men, and 79% higher than Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) men, who have the lowest sex-specific incidence. Overall incidence is higher in Black men largely because of prostate cancer, which is 70% higher than in White men, 3x times higher than in AAPI men, and 2x higher than in AIAN and Hispanic men.

AIAN and White women have the highest incidence rate of cancer—10% higher than Black women. But AIAN women have a 16% higher chance of dying from cancer than White women and Black women have a 12% higher chance. Most striking is that Black women have a 4% lower incidence of breast cancer than White women but are 40% more likely to die from it. Similarly, Black women are twice as likely to die from endometrial cancer as White women despite similar incidence.

These statistics don’t include either basal cell or squamous cell skin cancers because US cancer registries are not required to collect information on these cancers. These numbers do not account for the effect the COVID-19 pandemic has likely had on cancer diagnoses, but do include available data about the first year’s effect on cancer deaths.

- Helpful resources

- For researchers

For prostate cancer: American Cancer Society Guideline for the Early Detection of Prostate Cancer: Update 2010 Should I Be Tested for Prostate Cancer? Prostate Cancer Research Highlights Cancer Disparities Research Highlights For cervical cancer: American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Prevention and Early Detection of Cervical Cancer Patient Page: Vaccination for the Prevention of HPV HPV Vaccine 2020 ACS Guidelines The HPV Vaccine: A Powerful Way to Help Prevent 3+ Cancers in Women

American Cancer Society news stories are copyrighted material and are not intended to be used as press releases. For reprint requests, please see our Content Usage Policy.